History

Jayhawker and Collaboration

In 1933, Sinclair Lewis collaborated with Lloyd Lewis (no relation) to write a play revolving around the Civil War called Jayhawker. In the fall of 1934, the play, which in early drafts collected by Hubert Gibson was called “The Skedaddler” and “The Glory Hole,” was performed in Philadelphia, Washington, and New York. The play was not successful, closing just after a few weeks on Broadway. In 1935, the play was published in novel form... read more.

Harry Sinclair Lewis - (1885-1951)

Harry Sinclair Lewis, known to his friends as “Red,” was a prolific American novelist, short-story writer, and playwright. Born in Sauk Centre, Minnesota on February 7, 1885, to Edwin and Emma Lewis, Lewis had two older brothers, Fred and Claude. Main Street, published in 1920, is Lewis’ best known work... read more.

Lloyd Downs Lewis - (1891-1949)

After graduation, Lewis became a reporter for the North American in Philadelphia. In 1915, Lewis left Philadelphia for the Chicago Herald. During WWI, Lewis enlisted in the Navy and served for one year. Upon his discharge, Lloyd worked as a publicist and advertising director for the Chicago movie chain Balaban and Katz. In 1930, Lewis returned to journalism, taking a position with the Chicago Daily News as a drama critic. He eventually became the amusement editor, and, in 1936, became the sports editor. During this time, Lewis produced innovative sports writing by reporting on personalities and dramatic elements. In 1943, he was promoted to managing editor of the Chicago Daily News, a position he held until he retired in 1945. Lewis left to focus on his historical writing... read more.

Hubert Irey Gibson - (1906-1996)

The newly learned secretarial skills lead Hubert to his job with Sinclair and Lloyd Lewis in the fall of 1933. Chicago Daily News drama critic Lloyd Lewis, who was reported at the time to be writing a play with a famous author, gave Hubert a job as secretary. Hubert then lived temporarily with Sinclair Lewis at the Hotel Sherry in Chicago, preparing draft after draft of Jayhawker (which was then called “The Skedaddler” and “The Glory Hole”). While transcribing the manuscripts for Sinclair and Lloyd Lewis, Hubert was often called upon to act out many sequences in the play... read more.

Hubert Irey Gibson

(1906-1996)

Hubert Irey Gibson was born in Mason, Illinois, on December 21, 1906, the eldest of seven children.

Hubert Irey Gibson was born in Mason, Illinois, on December 21, 1906, the eldest of seven children.

As a child, Hubert enjoyed writing, dreaming one day to become an author. Not sure that he could make a living solely as an author, he eventually decided to be a lawyer who was a writer. In 1928, Hubert moved to Chicago to attend law school. While in school, he found employment as a law clerk. Unfortunately, as the Great Depression descended upon the country, Hubert found himself with a growing family and no job.

While Hubert’s wife, the former Frances Lauk, found steady work as a stenographer and typist, Hubert was unable to land employment. Frances suggested that Hubert gain skills that were in demand, such as typing and shorthand. So, Hubert attended night classes at a business college and soon acquired those skills.

The newly learned secretarial skills lead Hubert to his job with Sinclair and Lloyd Lewis in the fall of 1933. Chicago Daily News drama critic Lloyd Lewis, who was reported at the time to be writing a play with a famous author, gave Hubert a job as secretary. Hubert then lived temporarily with Sinclair Lewis at the Hotel Sherry in Chicago, preparing draft after draft of Jayhawker (which was then called “The Skedaddler” and “The Glory Hole”). While transcribing the manuscripts for Sinclair and Lloyd Lewis, Hubert was often called upon to act out many sequences in the play.

After his employment with Sinclair and Lloyd Lewis ended, Hubert was hired by Firestone Rubber Company in Akron, Ohio, as personal secretary to Harvey Firestone, Sr., and his son Harvey Firestone, Jr. He also served with the Firestone chairman John W. Thomas and executive vice-president J. E. Trainer. Hubert eventually became manger of Plant 1 in Akron. In 1954, Hubert became general manager of Firestone’s Guided Missile Division in South Gate, California.

In 1966, Hubert retired to Arkansas. He passed away in April 1996.

Hubert and Frances married in 1929 and had three children: Doris, Barbara, and David.

In October 2007, the Jayhawker manuscripts were donated by the children of Hubert and Frances Gibson (Doris, Barbara, and David) to the St. Cloud State University Archives.

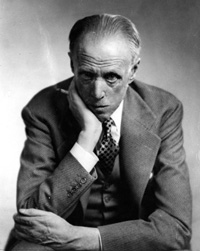

Harry Sinclair Lewis

(1885-1951)

Harry Sinclair Lewis, known to his friends as “Red,” was a prolific American novelist, short-story writer, and playwright. Main Street, published in 1920, is Lewis’ best known work.

Harry Sinclair Lewis, known to his friends as “Red,” was a prolific American novelist, short-story writer, and playwright. Main Street, published in 1920, is Lewis’ best known work.

Born in Sauk Centre, Minnesota on February 7, 1885, to Edwin and Emma Lewis, Lewis had two older brothers, Fred and Claude.

At Yale University, where Lewis received a degree in 1908, Lewis published in the Yale Literary Magazine, the Courant, and the Record. This began a long career of writing novels, plays, and short stories.

Lewis’ bibliography includes the novels:

Hike and the Aeroplane (1912) |

Mantrap (1926) |

The Prodigal Parents (1938) |

Our Mr Wrenn (1914) |

Elmer Gantry (1927) |

Bethel Merriday (1940) |

The Trail of the Hawk (1915) |

The Man Who Knew Coolidge (1928) |

Gideon Planish (1943) |

The Job (1917) |

Dodsworth (1929) |

Cass Timberlane (1945) |

The Innocents (1917) |

Launcelot (1932) |

Kingsblood Royal (1947) |

Free Air (1919) |

Ann Vickers (1933) |

The God-Seeker (1949) |

Main Street (1920) |

Work of Art (1934) |

World So Wide (1951) |

Babbitt (1922) |

The Jayhawker (1935) |

|

Arrowsmith (1925) |

It Can’t Happen Here (1935) |

|

Lewis turned down the Pulitzer Prize in literature in 1926, but accepted the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1930.

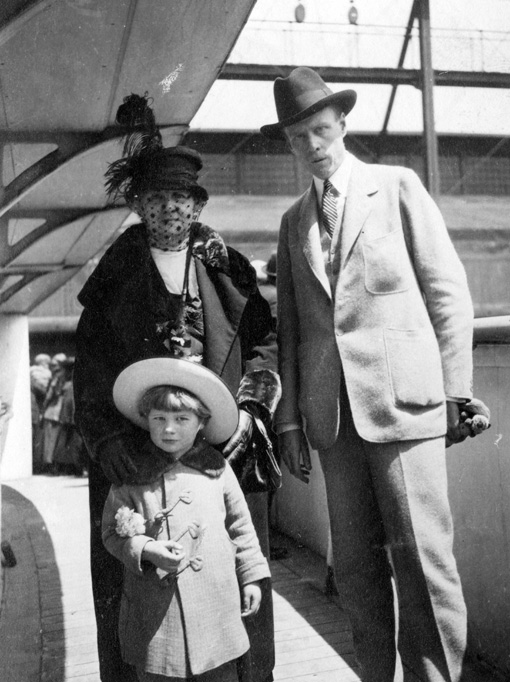

Lewis was married twice. He wed Grace Hegger in 1914, divorcing in 1925. They had a son, Wells, who was born in 1917. In 1944, Wells died in combat in France during World War II.

In 1928, Lewis married Dorothy Thompson, a well-known journalist in her own right. They had one son, Michael, who was born in 1930. They divorced in 1942. Lewis never remarried.

Lewis died in Rome, Italy on January 10, 1951. His cremated remains were interred in Sauk Centre, Minnesota.

There are many secondary sources for information about Lewis’ life, including Richard Lingeman 2002 book, Sinclair Lewis: Rebel from Main Street.

Lloyd Downs Lewis

(1891-1949)

Lloyd Downs Lewis was born May 2, 1891 in Pendleton, Indiana to J.J. Lewis and Josephine Downs. Lewis attended Swarthmore College, graduating in 1913.

After graduation, Lewis became a reporter for the North American in Philadelphia. In 1915, Lewis left Philadelphia for the Chicago Herald. During WWI, Lewis enlisted in the Navy and served for one year. Upon his discharge, Lloyd worked as a publicist and advertising director for the Chicago movie chain Balaban and Katz. In 1930, Lewis returned to journalism, taking a position with the Chicago Daily News as a drama critic. He eventually became the amusement editor, and, in 1936, became the sports editor. During this time, Lewis produced innovative sports writing by reporting on personalities and dramatic elements. In 1943, he was promoted to managing editor of the Chicago Daily News, a position he held until he retired in 1945. Lewis left to focus on his historical writing. He wrote several highly regarded historical books which include:

- Sherman: Fighting Prophet (1932)

- Oscar Wilde Discovers America, 1882 (1936)

- Myths After Lincoln (1941)

- Captain Sam Grant (1950), (completed by Bruce Catton after Lewis' death)

Lewis married Kathryn Dougherty, a well-known journalist in her own right, on December. 30, 1925. They had no children, but raised Nancy Anderson, the daughter of a friend of Kathryn's who had passed away. They commissioned friend Frank Lloyd Wright to design their home in Libertyville, Illinois near the Des Plaines River. The home was completed in 1939. Lloyd Lewis died unexpectedly of a heart attack on April 21, 1949.

Jayhawker and Collaboration

In 1933, Sinclair Lewis collaborated with Lloyd Lewis (no relation) to write a play revolving around the Civil War called Jayhawker. In the fall of 1934, the play, which in early drafts collected by Hubert Gibson was called “The Skedaddler” and “The Glory Hole,” was performed in Philadelphia, Washington, and New York. The play was not successful, closing just after a few weeks on Broadway. In 1935, the play was published in novel form

The collaboration began in early 1933. Sinclair Lewis and Lloyd Lewis met at a restaurant in Chicago through a mutual friend. Sinclair had recently read Lloyd’s writing about the Civil War and became convinced that the two should collaborate creatively.1 At the time, Lloyd was the dramatic critic for the Chicago Daily News.

Sinclair and Lloyd agreed to met in Chicago to write a draft of their Civil War play. Yet before that meeting, Lloyd already began to think about the play, which already had a title: The Skedaddler. In an April 1933 letter to Sinclair, Lloyd discussed gathering information about Jim Lane, “whose wild-jackass life and limitless political prowess and really superb tough-and-tumble oratory, our Senator can spring.” 2 Jim Lane was known as the leader of the abolitionist Kansas Jayhawkers movement, raising the “Kansas Brigade” for the Civil War. The play “was to deal with the Kansas-Missouri border raids before and during the Civil War; with the emergence, through oratorical bombast, of the first United States senator from Kansas, a wild roisterer not quite a criminal; with a scheme to end the Civil War through the seizure, by both parties, of Mexico; and with a love story.” 3

Sinclair and Lloyd agreed to met in Chicago to write a draft of their Civil War play. Yet before that meeting, Lloyd already began to think about the play, which already had a title: The Skedaddler. In an April 1933 letter to Sinclair, Lloyd discussed gathering information about Jim Lane, “whose wild-jackass life and limitless political prowess and really superb tough-and-tumble oratory, our Senator can spring.” 2 Jim Lane was known as the leader of the abolitionist Kansas Jayhawkers movement, raising the “Kansas Brigade” for the Civil War. The play “was to deal with the Kansas-Missouri border raids before and during the Civil War; with the emergence, through oratorical bombast, of the first United States senator from Kansas, a wild roisterer not quite a criminal; with a scheme to end the Civil War through the seizure, by both parties, of Mexico; and with a love story.” 3

Before his journey to Illinois, Sinclair pressed Lloyd to make arrangements for his stay. In a letter dated August 24, 1933, Sinclair asked Lloyd to find a stenographer “male, so we can work at night,” as well as a hotel for the duration.4 In another letter a few days later, Sinclair requested Lloyd to “[f]ind me a hotel suite not too far from your place, and we can devote it to work,” yet was concerned about the price. Sinclair wrote, “Don’t let ‘em stick me over $10.00 a day,” and urged Lloyd to keep their collaboration quiet until later.5

By the time Sinclair arrived in Chicago in September 1933, Lloyd hired Hubert Gibson to serve as their secretary as well as securing rooms at the Hotel Sherry in the Hyde neighborhood of Chicago. According to Sinclair Lewis biographer Mark Schorer, the purpose of the collaboration was to fuse “farce, satire, sentiment, and the spirit of the Gettysburg Address” into dramatic unity.6

How did they work? They took the play scene by scene. Sinclair and Lloyd “would discuss a scene thoroughly, improving speeches as they went, making notes, and then each man would write out a version of the whole.” Further, they would “exchange manuscripts, each would criticize the other’s, and then they would knock out a combination of the two.” Schorer suggested that Lloyd was responsible for the “substance of the scenes,” while Sinclair took on the love story and finalized all of the dialogue.7

Gibson supported Schorer’s belief. Gibson, in a 1955 letter to his daughter Barbara, thought that Lloyd knew the Civil War very well and the Jayhawker plot was his. Gibson wrote that Lloyd “could not make the words live and breathe” yet, Gibson continued, “[h]e [Lloyd] could – but not to the extent of his collaborator.” 8

Gibson recalled the process of working on Jayhawker and Sinclair Lewis as a person. Gibson wrote that after “intense periods of dictating and editing, he [Sinclair] would frequently start drinking steadily a quart or more of whiskey a day.” Gibson said that Sinclair “insisted that no good work was ever conceived in alcohol, and, strangely enough, he never tried to write during any of the heavy drinking spells – which were always climaxed by a day or more of hybernation [sic].” 9

Roger Forseth, an expert on writers and alcohol, argued that as far back as the late 1920s Lewis had “worked in order not to drink.” He “established a pattern, a pattern driven by his alcoholic affliction, of employing his writing for therapy. It had become a defense mechanism, a necessary means of physical as well as psychic survival. Therefore, literary quality was not the desideratum. He had to embark on a major project at once to keep from drinking and to justify – to earn – the subsequent binge.”

The result of their collaboration in September 1933 was a rough draft of the play. Compared to the 1935 printed version, the final manuscript was far from complete. The closest portion finished was the Glory Hole scene in Act 2. The rest of the play was well on its way, but far from done.

Between September 1933 and August 1934, the play was rewritten many times. In February, March, and April of 1934, Sinclair completely rewrote the play.10 In a letter to Lloyd Lewis, Sinclair described his work on Jayhawker. Sinclair wrote that “[n]ow is the first time when I have been able really to devote myself completely to the job – because it is the first time since the first drive on Burdette, immediately following as it did the completion of Work of Art [which Sinclair finished in the summer of 1933], when I have been really rested, and have enjoyed working.” 11 Rewriting continued until and while the play was put into production in August 1934.

Despite the evolution and rewrites of Jayhawker, the play already had a producer, John Henry Hammond, and a director, Joe Losey.

Production of Jayhawker was to begin in the winter of 1934. In February 1934, production of Brother Burdette was postponed until the fall of 1934, due to the unavailability of a “suitable” star for the title role.12 Sinclair, during the first part of 1934, mentioned several possible actors to take on the lead role of Ace Burdette, including James Kirkwood, Charles Laughton, Spencer Tracy, William Barrett, and Henry Mollison.13 Fred Stone, a “musical comedy star,” would eventually win the role.14

Production of Jayhawker was to begin in the winter of 1934. In February 1934, production of Brother Burdette was postponed until the fall of 1934, due to the unavailability of a “suitable” star for the title role.12 Sinclair, during the first part of 1934, mentioned several possible actors to take on the lead role of Ace Burdette, including James Kirkwood, Charles Laughton, Spencer Tracy, William Barrett, and Henry Mollison.13 Fred Stone, a “musical comedy star,” would eventually win the role.14

In July 1934, the play, now called Jayhawker, was close to production.15 Sinclair attended the rehearsals and was very pleased. In a September 1934 letter to Lloyd, Sinclair remarked that “[i]t looks as though the play were [sic] not only going to be a success but an enormous success.” 16 Sinclair also wrote that “I don’t know which is better – Joe Losey’s directing or Fred Stone’s acting.” So good in fact that at the climax of the play when Will is shot dead, Sinclair wrote, “At the death of Will this afternoon and Nettie’s reaction to it, I caught John Henry Hammond with a tear in his eye, but I didn’t see it any too clearly because I had one myself.” 17 Unfortunately, critics and audiences did not feel the same way.

The play opened in Washington, DC, on October 15, 1934. The audience found the play “amusing.” A review of opening night in Washington said the audience “was unable to appreciate its Civil War atmosphere because Fred Stone made the political wisecracks sound too much like the present day.” The review believed that the play attempts to encapsulate the Kansas politics of anti-slavery were well done, but Burdette’s actions were “too reminiscent of the technique of Messrs. [Theodore] Bilbo [governor and senator from Mississippi] and [Huey] Long [governor and senator from Louisiana] to let a Washington audience take them seriously.” 18

The Philadelphia opening was not much better. A review of opening night noted the continued revision of the play. The review stated that “Sinclair Lewis…is evidently learning with “Jayhawker” the truth of the allegation that plays are not written, but rewritten.” But the revisions did not help. Jayhawker, the review continued, needed to be more dramatic. It hoped that it is “reasonable to believe the stuff may be found before the play leaves Philadelphia.” Yet, the anonymous critic believed Jayhawker was worth saving. It said that the play has “everything – or at the very least, everything necessary – but a last act.” 19 Portions of Jayhawker, especially the third act, were rewritten before it left for New York

Unfortunately, the run in New York fared no better. A review of opening night at the Cort Theater thought the play had a good start, yet had a “scant of wind in the last act.” It continued that Sinclair and Lloyd Lewis “impale their drama on an idea in the last half of the evening.” The acting was “sturdy” yet the play was called wordy and presented staging problems. 20 Not exactly a rousing endorsement for a play written by a Pulitzer Prize winning author and a Chicago theater critic.

Despite the poor reception on Broadway, Sinclair wrote that Hammond and Losey “still think the play will go over,” yet agreed with reviewers that “the third act slides down hill pretty badly.” Sinclair did not believe anything could be done to improve it, writing to Lloyd that “I doubt there’s anything fundamental or important that we can do now.” 21 On November 24, the play quietly closed after less than three weeks.

Shortly before the final performance of the play, Sinclair acknowledged his critics. The author believed that critics “have been much kinder to me than I deserve, both with my novels and with my plays” and had no complaints against the critics. Sinclair thought the critics were doing their job and because of the critics, Sinclair wrote, many plays would go on if they were not so “clear-minded.” Yet he defended himself in trying to earn a living – he wrote that “I do not see how a man can put $50,000 into a play and not desire to get it back.” 22

The next year, the play would appear in book form, selling just over a thousand copies. 23

Sinclair was pleased about the collaboration with Lloyd Lewis. He wrote to Lloyd that, “[a] year and a half ago when I was in Chicago on my way back from California I had, as I had had for some years previous, a notion that I would like to find a perfect collaborator for a play dealing with a Civil War Senator and a boy who was his substitute. I met you one evening, and that not for so very long and in company with other people. I decided instantly that, if you should care to do it, you were the perfect collaborator. The amount of actual clock time involved in the decision was not large, and yet I do not feel that the decision was hasty and the event has proved me right.” 24

- Mark Schorer, Sinclair Lewis: An American Life (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961), 586

- Lewis, Lloyd. Letter to Sinclair Lewis dated April 30, 1933. Hubert Irey Gibson Collection of Sinclair Lewis. St. Cloud State University Archives, St. Cloud, MN.

- Schorer, 590

- Lewis, Sinclair. Letter to Lloyd Lewis dated August 24, 1933. Lloyd Lewis Papers. Newberry Library, Chicago, IL

- Lewis, Sinclair. Letter to Lloyd Lewis dated August 26, 1933. Lloyd Lewis Papers. Newberry Library, Chicago, IL

- Schorer, 590

- Schorer, 590

- Gibson, Hubert I. Letter to Barbara Gibson dated February 5, 1955. Hubert Irey Gibson Collection of Sinclair Lewis. St. Cloud State University Archives, St. Cloud, MN.

- Richard Lingeman, Sinclair Lewis: Rebel from Main Street (St. Paul: Borealis Books, 2002), 429

- Schorer, 598-599

- Lewis, Sinclair. Letter to Lloyd Lewis dated April 23, 1934. Lloyd Lewis Papers. Newberry Library, Chicago, IL

- “’Brother Burdette’ Deferred,” New York Times, 20 February 1934.

- Lewis, Sinclair. Letter to Lloyd Lewis dated April 23, 1934. Lloyd Lewis Papers. Newberry Library, Chicago, IL; Lewis, Sinclair. Letter to Lloyd Lewis dated May 8, 1934. Lloyd Lewis Papers. Newberry Library, Chicago, IL

- “Fred Stone in New Play,” New York Times, 18 August 1934.

- “Rialto Gossip,” New York Times, 22 July 1934

- Lewis, Sinclair. Letter to Lloyd Lewis dated September 21, 1934. Lloyd Lewis Papers. Newberry Library, Chicago, IL

- Lewis, Sinclair. Letter to Lloyd Lewis dated September 22, 1934. Lloyd Lewis Papers. Newberry Library, Chicago, IL

- “Fred Stone Appears in Political Play,” New York Times, 16 October 1934.

- “Ninety Miles from Broadway,” New York Times, 4 November 1934.

- Brooks Atkinson, “The Play,” New York Times, 6 November 1934

- Lewis, Sinclair. Letter to Lloyd Lewis dated November 9, 1934. Lloyd Lewis Papers. Newberry Library, Chicago, IL

- Sinclair Lewis, “Last Word,” New York Times, 18 November 1934.

- Schorer, 603

- Lewis, Sinclair. Letter to Lloyd Lewis dated August 21, 1934. Lloyd Lewis Papers. Newberry Library, Chicago, IL

Title: Title page of printed version of Jayhawker

Location: Miller Center Main Collection PS3523.E94 J3 1935

Title: Dust cover of Jayhawker

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 6a, folder 2

ID: 00149

Title: Hubert Irey Gibson, 1954

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Hubert Irey Gibson Collection of Sinclair Lewis, Box 2, folder 6

Title: Letter, Lloyd Lewis to Sinclair Lewis, April 30, 1933

Location: Hubert Irey Gibson Collection of Sinclair Lewis, Box 1, folder 21

Title: Letter, Lloyd Lewis to Sinclair Lewis, August 17, 1933

Location: Hubert Irey Gibson Collection of Sinclair Lewis, Box 1, folder 21

Title: Article about Hubert Gibson and his time with the Jayhawker, The Daily Signal, February 10, 1960

Location: Hubert Irey Gibson Collection of Sinclair Lewis, Box 2, folder 6

Title: Letter, Lloyd Lewis to Sinclair Lewis, September 8, 1933

Location: Hubert Irey Gibson Collection of Sinclair Lewis, Box 1, folder 21

Title: Letter, Hubert Irey Gibson to daughter Barbara, February 5, 1955, about his time working on Jayhawker (page 1)

Location: Hubert Irey Gibson Collection of Sinclair Lewis, Box 2, folder 4

Title: Letter, Hubert Irey Gibson to daughter Barbara, February 5, 1955, about his time working on Jayhawker (page 2)

Location: Hubert Irey Gibson Collection of Sinclair Lewis, Box 2, folder 4

Title: Letter, Sinclair Lewis to A.W. Davis, January 3, 1935

Location: Hubert Irey Gibson Collection of Sinclair Lewis, Box 2, folder 7

Title: Book Cover of Jayhawker

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 6a, folder 2

Title: Signed autograph from Sinclair to his brother Claude in a copy of Jayhawker.

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 6a, folder 2

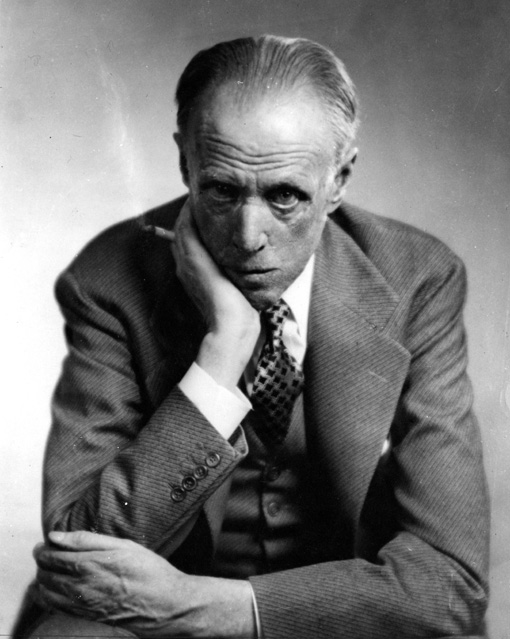

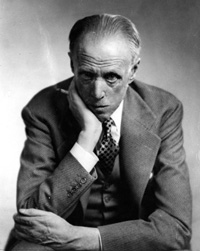

ID: 00116

Title: Sinclair Lewis, 1949

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 21, folder 8

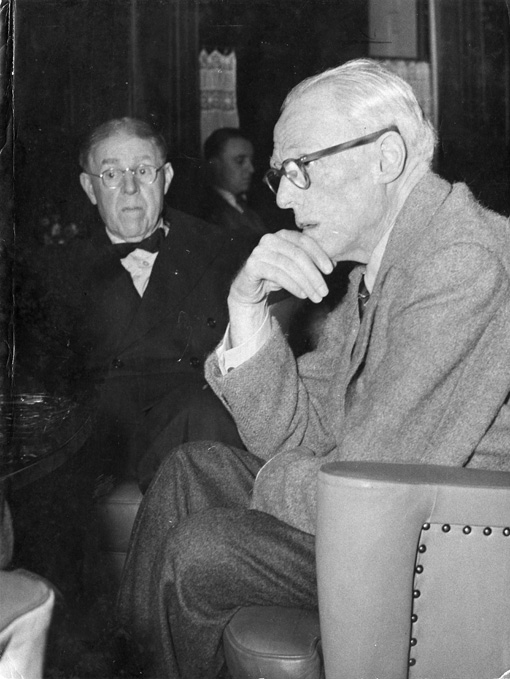

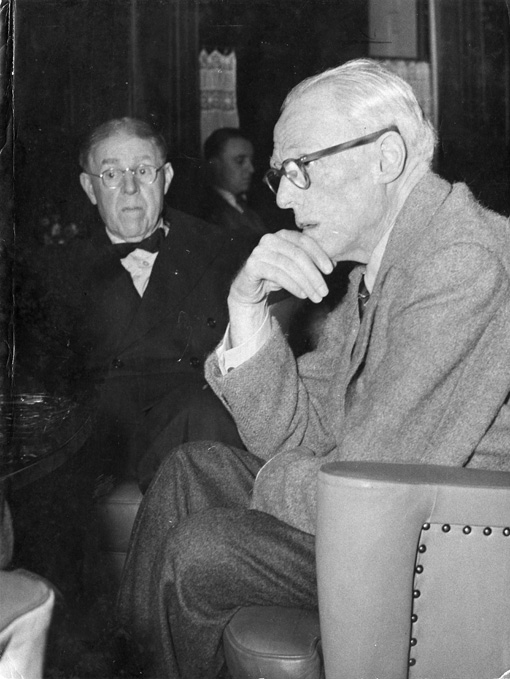

ID: 00230

Title: Claude and Sinclair Lewis, Amsterdam, 1949

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 21, folder 8

ID: 00913

Title: Sinclair Lewis in a bathrobe, 1920-1929

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 21, folder 8

ID: 00914

Title: Sinclair Lewis talks to a guide, 1920-1929

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 21, folder 8

ID: 00915

Title: Sinclair Lewis and friend, 1920-1929

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 21, folder 8

ID: 00916

Title: Sinclair Lewis, 1907?

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 21, folder 8

ID: 00917

Title: Sinclair Lewis, 1885

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 21, folder 8

ID: 00918

Title: Wells Lewis, 1920-1925; Wells was the son of Sinclair and Grace Lewis, born in 1917

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 21, folder 8

ID: 00919

Title: Wells Lewis, 1927; Wells was the son of Sinclair and Grace Lewis, born in 1917

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 21, folder 8

ID: 00920

Title: Sinclair Lewis, wife Dorothy Thompson and son Michael Lewis, 1930; Michael was the son of Sinclair Lewis and Dorothy Thompson, born in 1930

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 21, folder 8

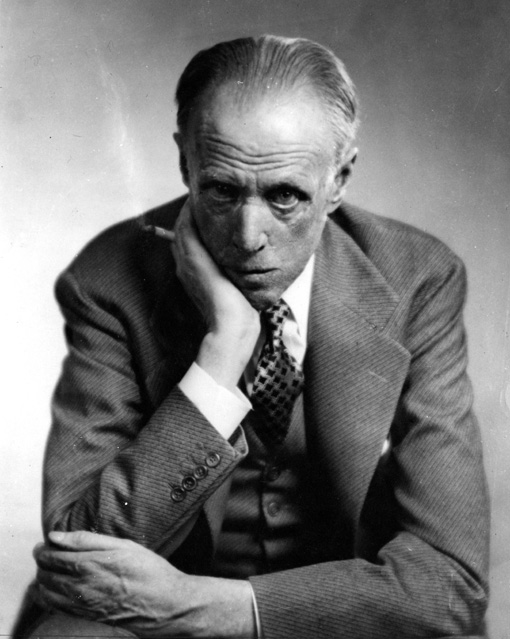

ID: 00934

Title: Sinclair Lewis, 1930-1939

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 2, folder 1

ID: 00935

Title: Wells Lewis, 1922; Wells was the son of Sinclair and Grace Lewis, born in 1917

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 2, folder 1

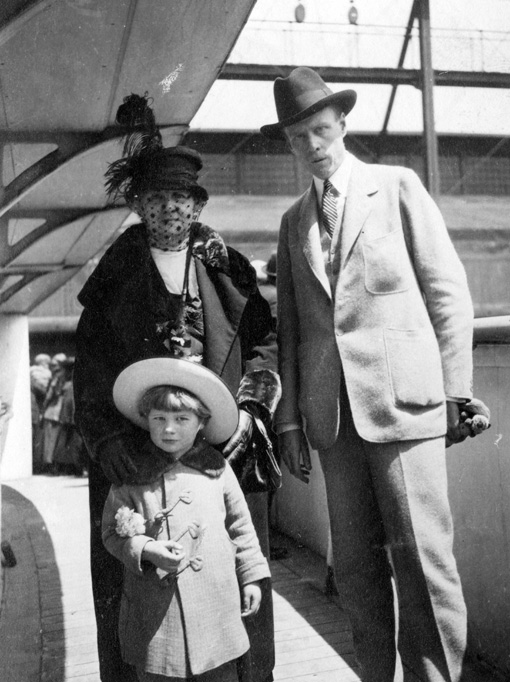

ID: 00936

Title: Sinclair Lewis, his mother-in-law, and son Wells leaving for Europe, May 17, 1921

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 2, folder 1

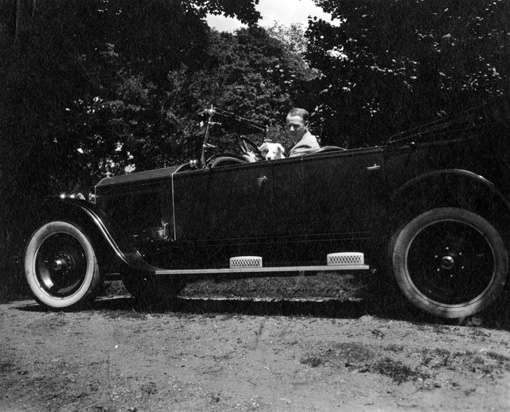

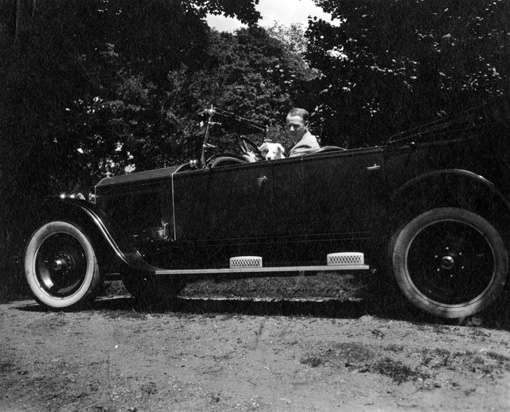

ID: 00937

Title: Sinclair Lewis sits in a car, 1920-1929

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 2, folder 1

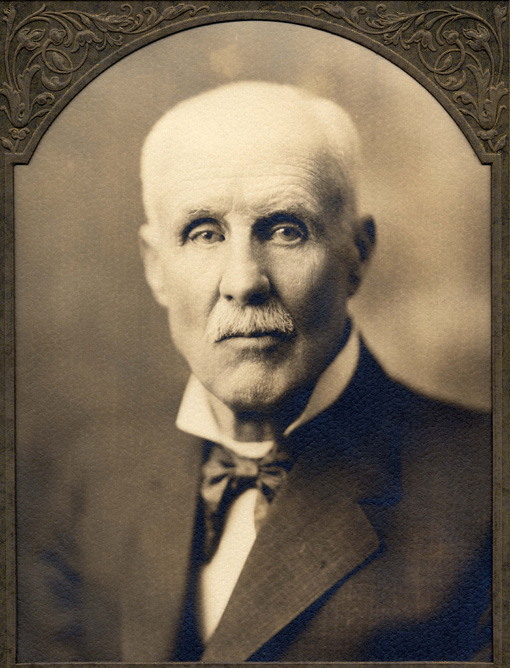

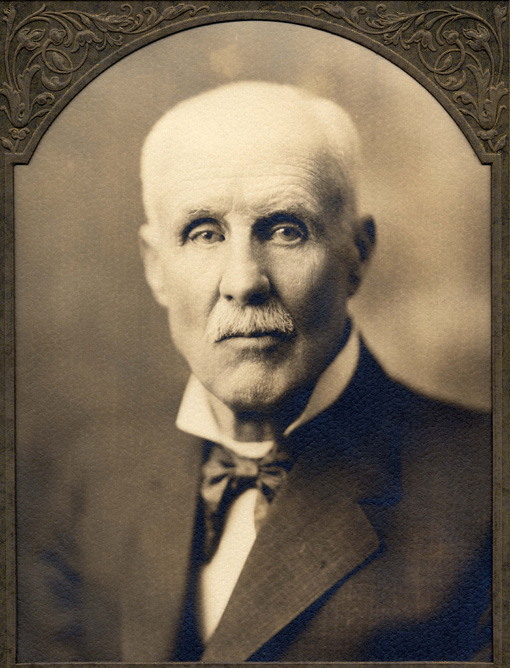

ID: 00938

Title: Edwin Lewis, 1900-1920; Edwin was the father of Sinclair Lewis

Physical Format: Black/white photo

Location: Lewis Family Papers, Box 2, folder 1

This site is provided for demonstration/education purposes only, as a proof-of-concept for an alternative presentation method for archival material, primarily drawn from the St. Cloud State University archives. It’s creation was through a "new researcher" grant from the Office of Sponsored Programs at SCSU, with the hopes of attracting additional funding to fully realize the complete, more robust site.

This site is provided for demonstration/education purposes only, as a proof-of-concept for an alternative presentation method for archival material, primarily drawn from the St. Cloud State University archives. It’s creation was through a "new researcher" grant from the Office of Sponsored Programs at SCSU, with the hopes of attracting additional funding to fully realize the complete, more robust site.